I prefer dangerous freedom over peaceful slavery Thomas jefferson Shirt

Or buy product at :teechip

-

5% OFF 2 items get 5% OFF on cart total Buy 2

-

10% OFF 3 items get 10% OFF on cart total Buy 3

-

15% OFF 4 items get 15% OFF on cart total Buy 4

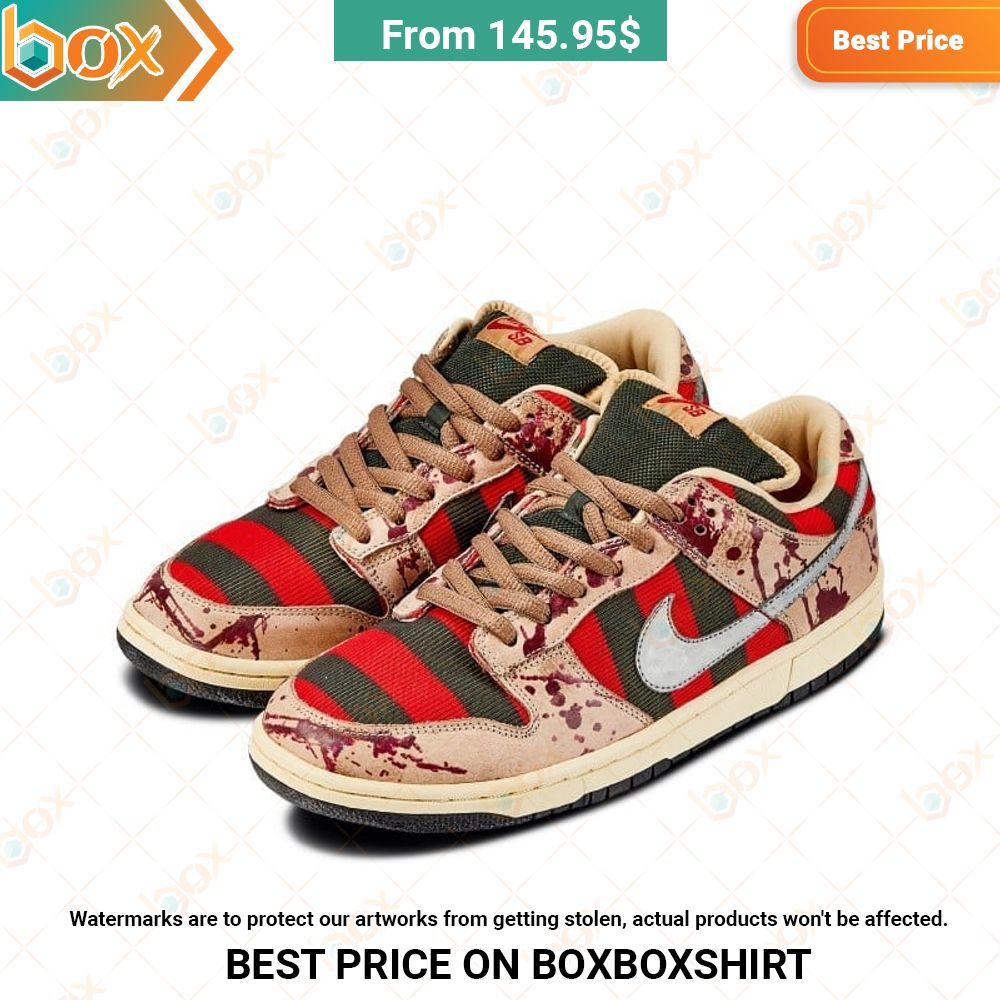

♥CHECK OUR BESTSELLERS - LIMITED EDITION SNEAKER FOR MEN OR WOMEN:

Best Selling Sneaker

Retro SP x J Balvin Medellín Sunset (UA) Air Jordan 3 Sneaker

Best Selling Sneaker

Best Selling Sneaker

Best Selling Sneaker

Table of Contents

ToggleI prefer dangerous freedom over peaceful slavery Thomas jefferson Shirt

The political upheaval of the years 1967 and 1968 and the rise of a new leftism (largely inspired by Neo-Marxism, later by French poststructuralism) did not change the intellectual profile and theoretical orientation of the Bielefeld School, now on their way to organize themselves as a special group with their own program. However, the political turn to the left and the push toward democratic reforms in West Germany largely helped to pave the way for the sudden and quick breakthrough of the new group at the beginning of the 1970s. Their common political background brought most of them in more or less strong relations to the social democratic party and the social liberal coalition, and many of them engaged in the heated public debates of the time about the German (Nazi) past and the interpretation of the Holocaust (the so-called ‘Historikerstreit’). They established themselves as public historians gaining high profile in the intellectual debates of West German democracy (Kocka and Budde, 2001; Wehler, 1988).

I prefer dangerous freedom over peaceful slavery Thomas jefferson Shirt

econd, the family-based framework of the informal economy provided a forum for learning a number of market-related skills and thus assisting the underground continuation of the interrupted embourgeoisement process. Such an underground preservation of officially denied values, attitudes, skills, and socioeconomic arrangements later proved crucial in the post-1989 systemic changes of returning to a capitalist/bourgeois track. Third, the informal economies of Eastern Europe complemented the ever-impoverishing state-run welfare provisions with community-based social services, and with slowly elaborated forms of secondary redistribution. Thus, they had a role in correcting the inadequacies of the distribution of incomes driven from the ‘first’ economy, and also in developing those market-conforming forms of social protection, which then, effectively, assisted the transition process amid the rapid withering away of state distribution some decades later. In short, the informal economy and the social relations around it gradually became a second – mostly hidden – regulator in the functioning of the communist regimes, and an important second pillar in organizing the daily life, well-being, aspirations, and life careers of substantial groups of Eastern European societies.

A. SHIPPING COSTS

Standard Shipping from $4.95 / 1 item

Expedited Shipping from $10.95 / 1 item

B. TRANSIT, HANDLING & ORDER CUT-OFF TIME

Generally, shipments are in transit for 10 – 15 days (Monday to Friday). Order cut-off time will be 05:00 PM Eastern Standard Time (New York). Order handling time is 3-5 business days (Monday to Friday).

C. CHANGE OF ADDRESS

We cannot change the delivery address once it is in transit. If you need to change the place to deliver your order, please contact us within 24 hours of placing your order at [email protected]

D. TRACKING

Once your order has been shipped, your order comes with a tracking number allowing you to track it until it is delivered to you. Please check your tracking code in your billing mail.

E. CANCELLATIONS

If you change your mind before you have received your order, we are able to accept cancellations at any time before the order has been dispatched. If an order has already been dispatched, please refer to our refund policy.

G. PARCELS DAMAGE IN TRANSIT

If you find a parcel is damaged in transit, if possible, please reject the parcel from the courier and get in touch with our customer service. If the parcel has been delivered without you being present, please contact customer service with the next steps.

No Hassle Returns and Refunds

Our policy lasts 14 days. If 14 days have gone by since your purchase, unfortunately we can’t offer you a refund or exchange.

To be eligible for a return, your item must be unused and in the same condition that you received it. It must also be in the original packaging.

Several types of goods are exempt from being returned.

Gift cards

Downloadable software products

Some health and personal care items

To complete your return, we require a receipt or proof of purchase.

Please do not send your purchase back to the manufacturer.

There are certain situations where only partial refunds are granted (if applicable) :

– Any item not in its original condition, is damaged or missing parts for reasons not due to our error

– Any item that is returned more than 30 days after delivery

Refunds (if applicable)

Once your return is received and inspected, we will send you an email to notify you that we have received your returned item. We will also notify you of the approval or rejection of your refund.

If you are approved, then your refund will be processed, and a credit will automatically be applied to your credit card or original method of payment, within a certain amount of days.

Late or missing refunds (if applicable)

If you haven’t received a refund yet, first check your bank account again.

Then contact your credit card company, it may take some time before your refund is officially posted.

Next contact your bank. There is often some processing time before a refund is posted.

If you’ve done all of this and you still have not received your refund yet, please contact us at [email protected]